There was no escaping Harry Potter in the late 90s; seemingly every child, and even a sizable number of adults, had been enchanted by the boy wizard’s nostalgically old fashioned adventures. The first book, known as Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone everywhere but the US, where it was released under the title Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone, didn’t take long to win several awards and reach numerous sales milestones impressively swiftly following its July 1997 launch.

Given that the most popular collectible card game at the time (and, of course, the first ever CCG to have been released), Magic: The Gathering, had magic right there in its name, as well as referring to player decks as spellbooks, it seemed obvious that there would be some form of crossover between Harry Potter fans of all ages, and players of CCGs. Given that the first Harry Potter book was released in 1997, and by 2000 there were already four books in the series, it’s odd that it took so long for the official Harry Potter Trading Card Game to arrive (it did, belatedly and briefly, in 2001; we’ve covered it in another Reshuffle feature, which you’ll find here).

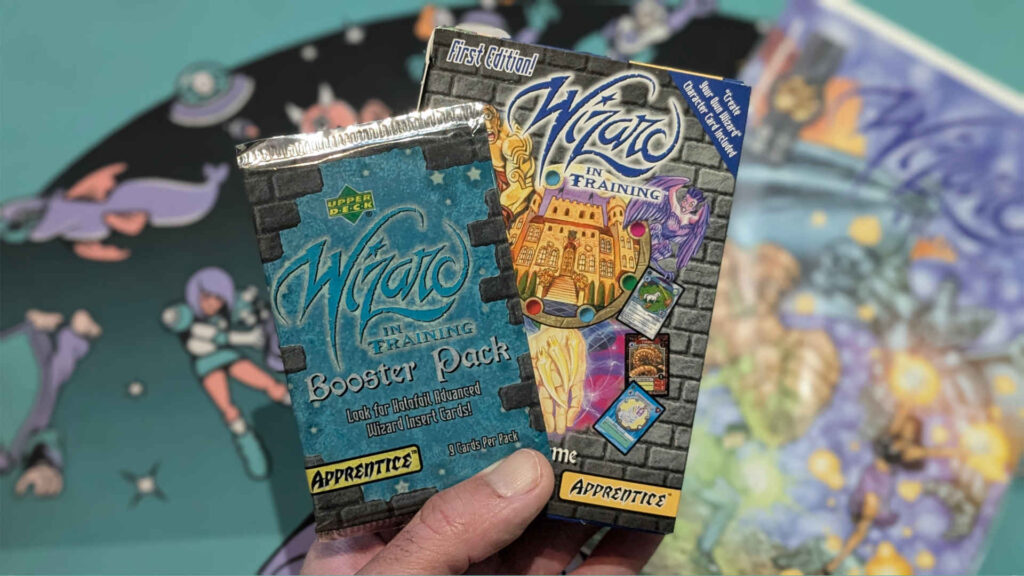

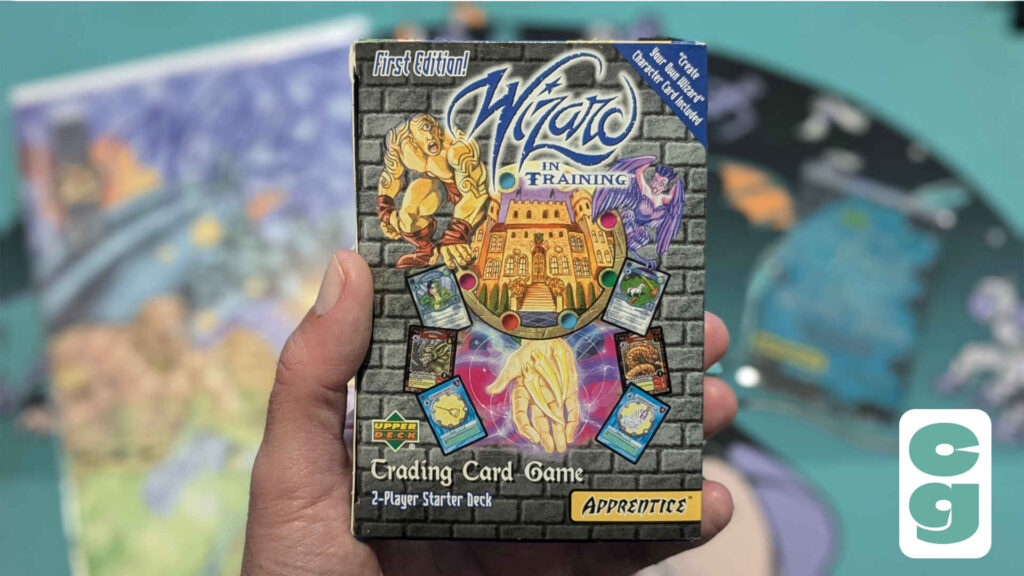

Upper Deck Entertainment noticed this glaring oversight, and as the Harry Potter books were becoming more and more popular, they released a very Harry Potter-esque trading card game, named Wizard In Training, in 2000.

Of course, you’d be forgiven for not being aware of Upper Deck’s blatantly plagiaristic ‘homage’ to Harry Potter, as it had an even shorter shelf life than the official Harry Potter Trading Card Game itself. So what went wrong, and did anything go right, with Wizard In Training? Let’s find out!

Table of Contents

ToggleGetting Started With Wizard In Training

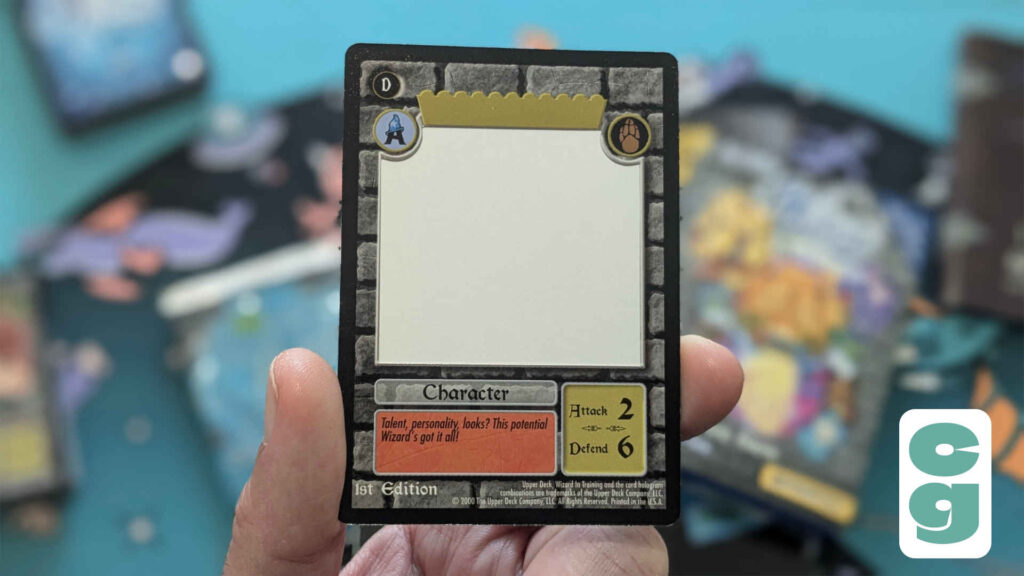

The entry point for Wizard In Training is its 2-Player Starter Deck set; this features 60 cards (enough for each of two players to have a 30 card deck), a rulebook and even a ‘Create Your Own Wizard’ card. The latter of which feels like a good way for players to just add Harry Potter, or any of their favorite characters from JK Rowling’s series, into the not-Harry Potter TCG. Of course, players can add themselves, or a completely original character, if they choose, with the dual-layered card, which features a completely blank square for a custom illustration.

There are four different types of card in Wizard In Training: Main Characters, of which each player has one to head up their deck (not unlike Leaders in Star Wars Unlimited, or Characters in UniVersus), Duel Characters, Spells, and Items. The rulebook is styled like a spellbook, and is called the “Book of Secrets.”

For the purposes of the Starter Decks, players will need to separate the cards into two decks, each of which has a fixed selection of cards and two Main Characters; players may choose which Main Character they play with, and their decks will then only have 29 cards in total during play. It’s worth noting that the 29 card decks are only applicable in the Starter; it’s a little odd that Upper Deck didn’t provide one extra card per deck to make it complete as per the rules. Of course, if using boosters to build decks beyond the cards included in the introductory set, decks will have 30 cards.

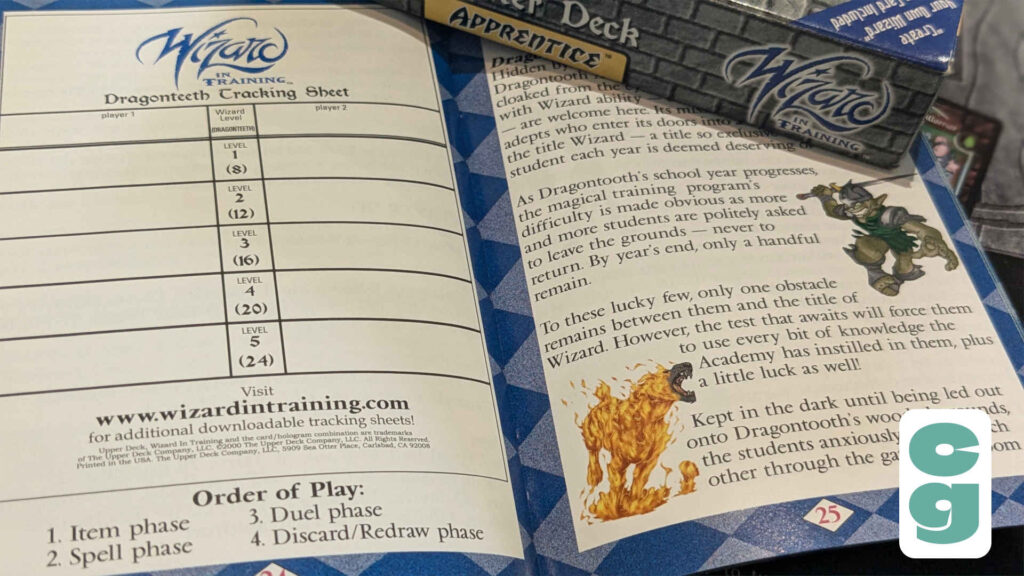

Once players have their decks and Main Characters (and have chosen which of their two Main Characters they’ll be using), drawn five cards from their decks (or ‘Resource Pile’ as the rulebook, perhaps unnecessarily, refers to it as), and they have a pen and paper, or other method, to track the number of Dragonteeth they acquire during the game, they’re ready to play.

How To Play A Game Of Wizard In Training

There are four phases to each turn in Wizard In Training. The first player will play through all four phases before play passes to the second player, and they then do the same before the first player takes another turn. These are: the Item Phase, the Spell Phase, the Duel Phase, and the Discard/Redraw Phase.

In the Item Phase, the active player will place all Item cards from their hand to the left of their play area, to create a Power Pool. This is to collect Dragonteeth; collecting enough Dragonteeth will allow you to proceed to the next Wizard level; each player starts at Wizard Level 1 (with zero Dragonteeth), and is attempting to collect enough Dragonteeth to complete the fifth level of Wizard training before their opponent, at which point they win the game.

There’s a bit of a counter-intuitive element to the Wizard levels; at Level 1, you must collect eight Dragonteeth to proceed to Level 2, then at Level 2 you need 12 Dragonteeth, 16 to complete Level 3, 20 Dragonteeth in order to complete Level 4 and, finally, you need 24 Dragonteeth to finish your Level 5 training, at which point you win. Doesn’t sound so confusing, right? Except the total of Dragonteeth is not cumulative, meaning that you begin each new level of training with zero Dragonteeth, and no Dragonteeth carry over if you manage to exceed the total on your way to completing your current level. It’s an utterly baffling, very confusing design choice that takes a while to truly grasp, and feels entirely unnecessary. Why not just amend the totals needed for each level?

In any case, that one rule shows that we’re hardly off to the strongest of starts with Wizard In Training, and the fact that you simply play all Item cards from your hand during the Item phase removes any element of strategy from the equation; you just play all Items to create a Power Pool, which gives you the number of Dragonteeth you have in the play area, by calculating the numbers on the top right of each Item card (which is a point that is very poorly explained in the rulebook, in terms of how this works per turn and cumulatively).

However, the Spell Phase is a bit more involving, in that you can choose to use a Spell to take Dragonteeth from their opponent, or to change the outcome of a Duel that may be about to take place. Each Spell has a Level requirement, and as long as the player is at or above the level on the card, the Spell can be cast, and its effects enacted. Some Spells require that players have a specific Item in order for them to be cast; if that’s the case, players simply equip their Main Character with the Item from their Power Pool. Of course, if they don’t have the Item, the Spell cannot be cast.

Players being targeted by Spells can defend with a Counterspell; the types of Spell that another Spell can counter are listed under ‘Counterspell Identifier’ on each Spell card. Players declare whether they’re using the immediate or duel effect of a Spell if it’s not countered; an immediate effect usually means taking Dragonteeth from your opponent and adding them to your own total, whereas duel effects can hinder the opponent’s Duel Character, or help your own, for example.

The Duel Phase sees the active player taking on the opponent in a Duel; first, the active player places a Duel Character face down in their play area (it must be on or below their current level), then the opponent can do the same in theirs. Before they’re turned face up, the Duel Characters can be equipped with a weapon or defend Item, from the Power Pool, if they’re capable of using one. An attached weapon always adds +2 to a Duel Character’s attack, and a defend Item adds +2 to their Defend number.

Don’t have a Duel Character to defend with? Well, then your Main Character must participate in the Duel, with the risk of losing a whole Wizard level if you lose. Oh, and if you don’t have a ‘legal’ Duel Character in your hand to use, you may play a higher level Duel Character than your current level allows, but this is at the cost of not being able to equip any Items, and also subtracting 1 from both Attack and Defend values for that Duel.

To determine the outcome of a Duel, players subtract their opponent’s Defend from their Attack value, and the highest result of the two calculated numbers wins the Duel. In another fairly convoluted touch, the winner of the Duel gains Dragonteeth equal to the sum of the defeated Character’s Attack and Defend numbers, though unlike with Spells, the Dragonteeth are not taken from the loser, just won outright. The winner can return their Items to their Power Pool, and the loser’s Items are discarded. If the result is a tie, the attacker loses one Dragontooth and Items are all returned to their Power Pools.

There are some very odd rules about “owing” Dragonteeth if you can’t pay, and it’s another fairly convoluted set of rules that means you have to also keep track of Dragontooth debt on your score tracking sheet, which just makes the whole game a lot less fun, and a lot more about bookkeeping, than it may seem on the surface.

Moving on to the last step of each player’s turn, we have the Discard/Redraw Phase, which allows players to discard any cards they don’t want from their hands, then draw a new hand of five cards. Any Spell or Duel Characters left in play are discarded.

How To Win A Game Of Wizard In Training

Play continues until one player has collected 24 Dragonteeth, when at Wizard Level 5; though this initially seems straightforward, of course this means starting from zero Dragonteeth once reaching level 5, then collecting a further 24 Dragonteeth!

The Art Of Wizard In Training

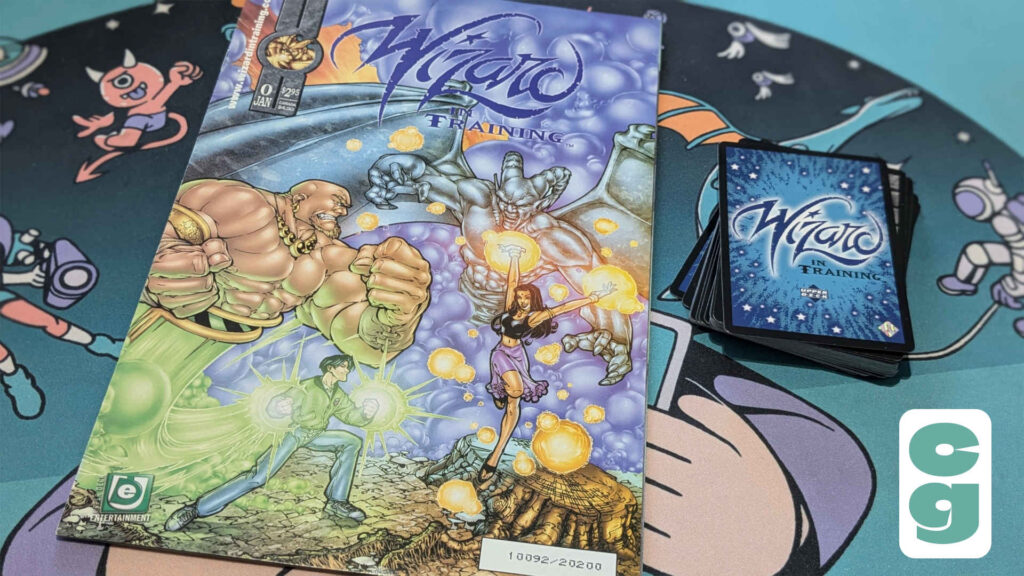

Perhaps the strongest element of Wizard In Training is the art; though it looks fairly generic at a distance, upon closer inspection the character and creature design is often genuinely excellent, with artwork that wouldn’t look out of place in, for example, a comic book. Which is a good time to mention that Upper Deck even went so far as to produce a limited edition, serial-numbered comic book to promote the game’s launch!

Wizard In Training Had A Comic Book Tie-In?

That’s right, Upper Deck was pretty serious about Wizard In Training, and really went all out in creating a world for the game, so as not to be simply cast as a cynical imitation of Harry Potter. In truth, it still can’t quite escape that characterization, but it’s impressive that Upper Deck even went as far as creating a comic book which introduces readers and players to the trading card game.

Though just like the card game itself, the comic book was short-lived (only one issue, numbered as issue #0, which generally denotes a prequel or set up for a series), it’s a form of promotion that we wouldn’t expect from an entirely new intellectual property, even now, and it’s definitely something that Upper Deck should be commended in going the extra mile for. Even the game’s rulebook features some really nice storytelling that gives the setting and its wizards some character beyond their illustrations, and there’s definitely some charm in the lore provided.

Is Wizard In Training Fun To Play?

Here’s the moment of truth: why didn’t Wizard In Training manage to cast a spell on gamers? Sadly, it’s just not a very good game at all. There are some ill-thought out, poorly judged rules, a strangely, incredibly restrictive deckbuilding system (which specifies the exact number of Spells, Duel Characters, and Items your deck must have, and almost entirely forbids the use of duplicate cards, aside from being able to use two Item cards of the same type) and, perhaps most egregiously of all, it really doesn’t do enough to move beyond looking and feeling like a dollar store Harry Potter game.

A lot of effort has gone into worldbuilding and creating a setting for Wizard In Training, but it all feels very derivative and not especially exciting. If the game had been stronger and featured more compelling, or even better designed mechanics, it likely would have held its own, even against the impending, official Harry Potter Trading Card Game. As it is, or rather was, it feels like a cynical commercial ploy in search of a game to hang onto. Elements such as tracking Dragonteeth feel especially poor, and the score sheet provided, along with the game’s order of play aid, is found on a random page in the rulebook, meaning that even that is impractical to use.

The game isn’t particularly clear about how Dragonteeth are collected or accrued using your Item cards; you really have to pay attention to other areas of the rulebook to figure this element of the game out, as it’s not properly described in the specific Item Phase section. Considering that element of the game is how you track your progress during the game, it’s shocking that this part of the rules is so badly articulated. One thing that is obvious is this: most of the work done for the game was in its visual look and lore; the game itself really does feel like an afterthought.

What Happened To Wizard In Training?

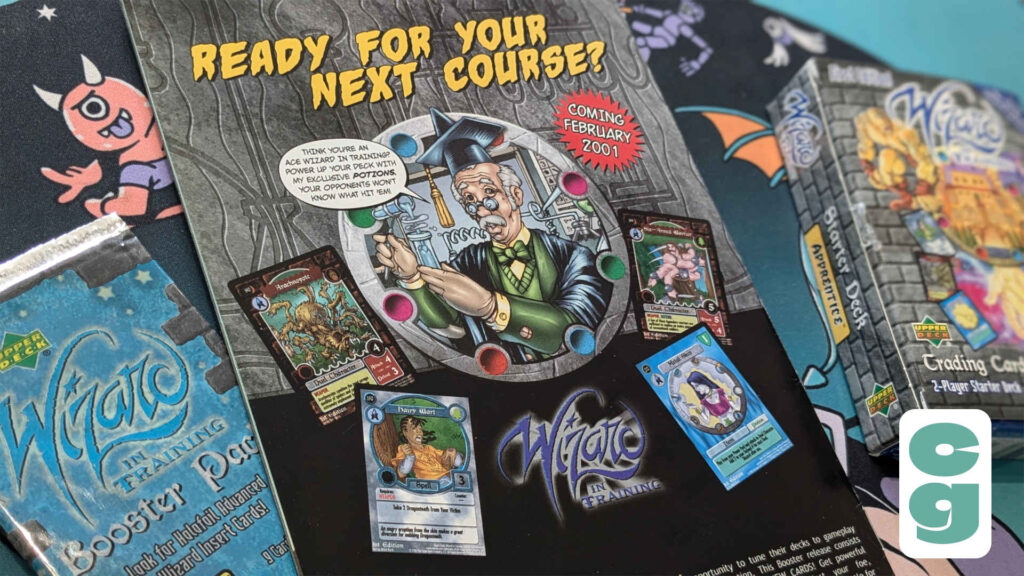

After the base set was released, just one further set, Professor Ploog’s Prize Potions, hit store shelves, and this booster expansion featured Advanced Duel Characters and even introduced Potions, a new Item card type. But it was too little, too late. The game just wasn’t enjoyable, or particularly playable in its released state, and to make matters worse for Upper Deck‘s apprentice-wizards-at-high-school game, the official Harry Potter TCG was soon launched, and was a genuinely excellent game from top to bottom, including its lavish presentation. Wizard In Training was suddenly and unceremoniously not the only place that gamers could play at being Harry Potter; worse still for Wizard In Training, fans could actually be Harry Potter in the other game, and not a pale imitation.

So it’s another trading card game that’s been largely forgotten, and despite the almost plagiaristic nature of Wizard In Training, I still think it’s a shame that it ended up being such a disappointment. The game could have provided a real alternative to younger players, especially before the Harry Potter Trading Card Game emerged, but even when its big name rival was released, the official game didn’t even last that long itself, thanks to some issues around its artwork that have become more difficult to investigate over time. As it is, Wizard In Training seems to have been a lesson that, no matter how attractive, well designed, or in-depth a game’s setting is, without a solid framework of game mechanics, players won’t stick around for long.

Want to find out more about old card games that you may not have seen or heard of before? Not all of them were poor imitations of other games, and some were cut short before their time despite excellent mechanics and clever game design. Check out our look at the Tomb Raider CCG, or our dive into Sim City: The Card Game, both of which successfully adapted popular video games into the collectible card game format.